In this article, I will show you the spine anatomy. Understanding the anatomy of the spine is essential if you want to assess posture, for example. If you are interested in assessing the posture, the linked article might be helpful.

Spine anatomy – General info on the spine

The spine (lat. “columna vertebralis”) lies between the head and the pelvis and makes up about two-fifths of the total height of a human being. The intervertebral discs (also called intervertebral discs; Latin “disci intervertebralis”) account for around 25% of the length of the spine. The spine consists of 24 freely movable vertebral bodies (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine) and two sections where the vertebral bodies are fused or grown together. The freely moving vertebral bodies are all located above or in front of the sacrum. They are, therefore, also referred to as “presacral” vertebrae (Latin “prae” ≙ “before”; “sacral” ≙ “concerning the sacrum”). As the name already suggests, the intervertebral discs lie as intervertebral discs (lat. “discus intervertebralis”, sg.) between adjacent vertebral bodies of the freely movable spine. There are typically 23 intervertebral discs in the free-moving area. There is no intervertebral disc between the first two cervical vertebrae because the vertebrae are built up slightly differently and are, therefore, connected to one another in a slightly different way. The spinal column sections after the freely movable area are the sacrum (lat. “os sacrum”) and the coccyx (lat. “os coccygis”). These sections cannot move freely because the original vertebral bodies have grown together.1–3

If you look at the spine from the side (see Fig. 1), you will see that the spine does not run straight from top to bottom but is curved in a particular direction in different areas.1–3 We are talking about a double S-shape of the spine.2 These typical spinal curves are essential e.g., to absorb shocks. The curvatures are referred to as lordosis and kyphosis. A lordosis describes a curvature that curves outwards in the abdominal direction. A kyphosis runs in the other direction and thus describes a curve that curves outward toward the back.1–3 The following spinal segments show a specific curvature1–3:

- Cervical spine: Lordosis

- Thoracic spine: Kyphosis

- Lumbar spine: Lordosis

- Sacrum: Kyphosis

In a later post, I will also explain the structure of the vertebrae in detail. In the following, I will give you a general overview of the spine’s structure and describe its different sections and their essential characteristics.

Spine anatomy – The individual sections

Spine anatomy – Cervical spine

The first 7 vertebrae make up the cervical spine when building the vertebral column. The typical designation of cervical vertebrae includes the letter “C” (“C” ≙ “cervicalis” ≙ “belonging to the neck”). The first cervical vertebra is, therefore, referred to as C1. In addition, the first cervical vertebra bears the name Atlas (the Titan carries the world on his shoulders, and C1 carries the head), in keeping with the titan of the same name from Greek mythology. C1 and C2 have a different structure than C3 – C6. And there is no intervertebral disc between C1 and C2. The last cervical vertebra, C7, also has a slightly different structure than C3 – C6 and, with its spinous process as the last vertebra in the cervical region, is usually quite easy to palpate.1–3

Spine anatomy – Thoracic spine

The thoracic spine consists of 12 vertebrae. The typical designation of thoracic vertebrae includes the letters “Th” (“Th” ≙ “thoracalis” ≙ “concerning the thorax”). All 12 thoracic vertebrae are also in contact with the 12 ribs. The vertebrae of the thoracic spine are more prominent and thicker than the cervical spine vertebrae.1–3

Spine anatomy – Lumbar spine

The last 5 freely moving vertebrae form the lumbar spine. The typical designation of lumbar vertebrae includes the letter “L” (“L” ≙ “lumbalis” ≙ “belonging to the loin”). Due to the higher loading in the spine’s lower parts, the lumbar region vertebrae are significantly larger than the rest.1–3

Sacrum

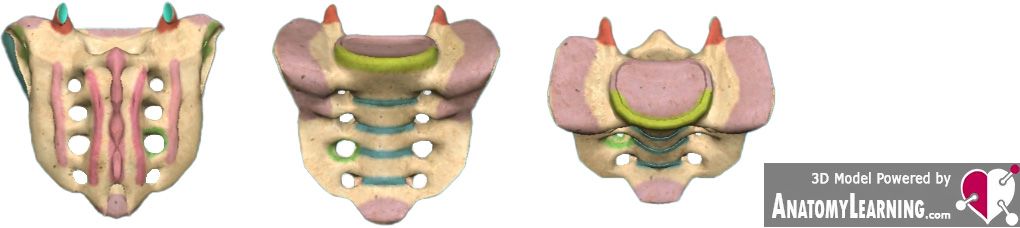

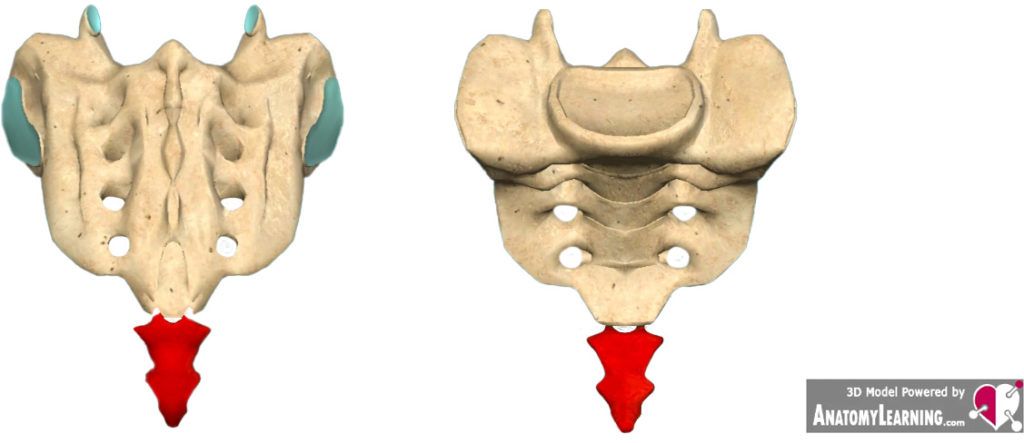

The sacrum connects to the lumbar spine. Figure 2 shows that the sacrum is almost triangular in shape and consists of 5 fused vertebrae (melted together during physical development). The typical designation of sacral vertebrae includes the letter “S” (“S” ≙ “sacralis” ≙ “belonging to the sacrum”). Between L5 and S1 is an intervertebral disc that curves furthest into the pelvis. The contact surface for the intervertebral disc on the sacrum is the base of the sacrum (“basis ossis sacri”). The front edge of the base, together with the intervertebral disc, is called the promontory (“promontorium ossis sacri” ≙ “protrusion of the base of the sacrum”). The sacrum has an articulated connection to L5 – the lumbosacral joint. In addition, the sacrum and subsequent coccyx form a joint – the sacrococcygeal joint.1–3

Coccyx

The coccyx (Fig. 3) is the spine’s last section connecting to the sacrum (Fig. 3).1–3 The coccyx typically consists of 4 fused vertebrae.3 However, the number of fused vertebrae can vary between 3 and 5.1,2 The size of the vertebra decreases downwards, whereby only the first coccygeal vertebra has some resemblance to the usual structure of a vertebra.1

There’s more information on my YouTube channel (in German) and Instagram profile (English)! And especially on YouTube, you will find cool exercises for your core. 🙂

Literature

- Sobotta, J. Sobotta, Atlas der Anatomie Band 1: Allgemeine Anatomie und Bewegungsapparat. (Urban & Fischer in Elsevier, 2017).

- Waschke, J., Böckers, T. M. & Paulsen, F. Sobotta Lehrbuch Anatomie. (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2019).

- Palastanga, N. & Soames, R. Anatomie und menschliche Bewegung – Strukturen und Funktionen. (Elsevier, Urban & Fischer Verlag, 2015).

Be the first to comment